- Home

- Joseph Bruchac

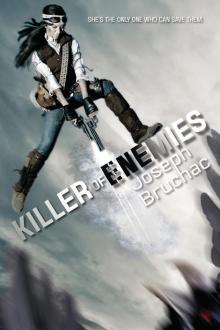

Killer of Enemies Page 8

Killer of Enemies Read online

Page 8

Screw you, sweetie.

“Am I to understand that you have successfully dispatched all of those large nasty flying nuisances?”

“Yes.”

“Ahhhh.”

She seems about to say something more. But then she raises one hand, commanding silence. As if I was about to say anything more, which I was not.

Lady Time pivots like a dancer, faces the wooden Swiss clock on the wall to her left. The minute hand, which I now notice is set one minute ahead of all the other clocks, moves to the twelve with a loud click that is audible even above the din of ticking and tocking, clicking and clacking that surrounds us.

Whirrr. Thunk!

A gear turns. A door flings itself open below the clock face. A garishly painted yellow bird thrusts itself and opens its wooden beak with a clack.

CUUU-KOOO, CUUU-KOOO, CUUU-KOOO.

Whirr. Thunk.

The bird whips back inside. The door snaps shut.

Lady Time raises her arms and then pirouettes a full circle and a half so that she is again facing me when she stops.

“Perfect. Wasn’t it?”

Which? The clock? Her twirl?

But I sense it is a rhetorical question that I am not expected to answer, especially since that extra minute has now passed. Every other clock in the room, dozens and dozens of them, is making its own little whirring, clicking, clacking, and brrring sounds that presage its forthcoming proclamation of time.

DING DING DING!

CLANG CLANG CLANG!

WHONG WHONG WHONG!

BONG BONG BONG!

Thank God, I think, that I wasn’t brought here at noon or midnight. I feel deafened by the din, which is clearly music to the ears of Lady Time, who is still waltzing or gavotting or polkaing—or whatever the hell it is that she thinks she is doing—after the last bell sounds.

Almost. From the far corner of the room another clock suddenly whirrs and then, twenty seconds late, sounds the hour.

Bing! Bing! Bing!

It almost sounds embarrassed to be so out of sync with the others. I almost laugh.

Lucky that I don’t.

Lady Time is not amused. A low growl emanates from that mask.

“WALTER!” she screams. I can’t see her face, but I have no doubt that it is red with rage.

A small, thin man wearing a robe comes running from somewhere at the back of the big room, the errant clock his destination.

“No!” Lady Time says. Not loudly at all, but the coldness in her voice is even more threatening than her scream. “Here!”

The little man runs forward and stops five feet short of her as if he has come against an invisible barrier. His features are small for his round face, but they display on them the amount of terror that I suspect is appropriate for this moment. Sweat beads are popping out on his pale brow, and his empty hands are lifted up in front of himself as if he is holding a shield.

“Have I not told you?” Lady Time says.

“Yes, your grace,” Walter replies in a voice that is deeper than you would expect from someone who can’t be more than five feet tall. There’s also pain in that voice, as if he is already experiencing the agony that he expects will soon be inflicted upon him.

“Three times,” Lady Times says, her voice even more cold, more calm than before.

She looks at his hands. And as she does so the fear on his face becomes even more visible. Then she shakes her head.

“No, you need all those fingers, don’t you, little timekeeper? To keep my lovelies wound and running . . . on time? All of them, except for my sweet little cuckoo, right on time?”

“Yes, your grace.”

“Toes . . . ,” she says to herself. “No. Can’t have you limping about caring for my sweethearts, can I?”

“No, your grace.” Walter’s voice is beginning to sound less frightened. And his thoughts suddenly come to me as clearly as if he was speaking them.

Perhaps the punishment will not be that terrible. Perhaps the bitch queen will just whip me again. I can stand a whipping. I can. I can. I can. Oh, how I wish I could pull the hands off that grandfather clock and drive them into her evil eye and blind her. Into her ears and deafen her. Yes! Yes! Yes!

“Teeth,” Lady Time says. Her voice is light and happy again. She twirls and signals to the three guards who have remained behind me at the door.

As they step forward, Walter seems to grow even smaller and his thoughts become an incoherent, horrified babble.

“Two—no, three,” Lady Time says. “Back teeth. I hate the look of missing teeth in front. And do it downstairs. I do so hate the sound of screaming.”

Two of the guards lift Walter up by his arms.

I stay where I am, looking to neither one side nor the other as they drag the whimpering timekeeper past me and shut the door behind them.

Lady Time turns back to me.

“Oh,” she says. “And who might you be? And what just punishment shall we mete out to you today, my dear?”

She’s crazy, I think, but not that crazy. I stay as I am in my At Ease pose, even though my mind is not at ease right now.

Lady Time laughs, a laugh that goes on a little too long as she whirls and spins like a wheel in one of her clocks.

Finally, she stops and holds her palm out toward me in a way that makes me think of a picture I saw in a tattered book of fairy tales. The witch offering candy to Hansel and Gretel.

“Oh my, I am just joking, my dear. Of course I know who you are. You are here to be praised for your good work.”

She pauses. Time for me to say something.

“Thank you,” I reply in a level, expressionless voice.

“You are a bit dull, aren’t you?” Lady Times says. Rhetorical. No reply needed. “But you are good at doing what you do, aren’t you? Ridding us of large nasty things? Yes?”

Reply expected.

“Yes.”

“Well then. Keep at it.”

She waves her hand. Audience over. The one remaining guard steps forward to escort me from her room.

But as I leave, Lady Time’s parting thoughts come unbidden to my mind. And they are less crazy than I might have expected—and more chilling.

That one bears watching. She may be more clever than the other three—fools that they are—give her credit for. She is useful. Yes. But dangerous as well. We do have her family as leverage, but will that always be enough? For a moment there she looked as if she was thinking about leaping at me and tearing out my throat! Put her down? Perhaps not yet. There may be more little jobs for her to do. Then . . .

Lady Time’s thoughts move away from words in her mind to several very graphic images—quite pleasing to her—of what she plans to have done to me when she decides I have outlived my usefulness.

I am living on borrowed time.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Where the Heart Is

As I walk down the tier toward my home—cell, that is—I am taken aback by what I see. The door is open. The lock hangs freely from the bike chain. But only four people know the combination to my lock. Me and . . . I catch the familiar scent of herbal soap.

I look inside and take a relieved breath when I see who is there waiting as quietly as guests at a surprise party. Despite Lady Time’s reservations about me, her haughty thank you is not my only reward after all. This place really does feel like home right now. The place where my heart lives as long as they are here.

“Mom! Ana! Victor!”

“Lozen!”

“Big Sis.”

We wrap our arms around each other in what my dad used to call our Old-time Apache Hug.

“How long?” I ask.

“Until the lamps are lit,” Mom says.

That’s about four hours. A longer time than we’ve been allowed to spend together in weeks.

Mom steps back and examines me carefully. “Your face is all bruised,” she says. I like it that she says it without pity or even surprise. Just making an observation. She reaches

down to the pouch at her belt and brings out a jar of salve as I look into the small mirror taped to my wall.

She’s right. My forehead is covered with a purple and yellow contusion. I have two black eyes and my chin is red and scraped. Amazingly, though, where the monster bird slashed my cheek, there’s nothing. Not even a scar. Lozen’s spring healed it completely. I guess I should have immersed my whole face in that medicine spring.

I look like a second-rate fighter after twelve rounds in the ring. All-out, bare knuckle combat, by the way, is one of the few sports that we are allowed here in Haven. Not that we enjoy it all that much. Since it is done for the pleasure of the Ones, it usually involves some poor outclassed ordinary getting the crap kicked out of him by one of the better trained and medicated guards. The best of them are Red, Lady Time’s heavily tattooed head mercenary, and Big Boy, who heads Diablita’s crew. Both Chainers, of course. Edwin is the third best ring fighter here, and as one of Diablita’s men under Big Boy’s tutelage he has been training in the hopes of beating Red.

“Sit.” Mom points to the bed.

I sit while Mom applies the salve to my forehead, my chin, around my eyes. The salve is comfrey plus a few other herbs whose uses were taught to Mom by her grandmother. But it’s not just the salve that is healing. It’s also Mom’s touch and the wordless chant she sings under her breath. I can feel my insides growing cool, my mind slowing down, the balance I didn’t know I was missing returning to me. I know that salve and Mom’s healing hands will do the job. In a day or two the bruises will be gone.

While Mom ministers to me, Victor and Ana sit quietly on the floor by my feet. To someone else outside of our family it might look like they are doing nothing. But they are actually doing something important: simply being with each other and with me.

“Anywhere else?” Mom asks.

I look at my arms, which had been covered with scrapes, cuts, and bruises yesterday. I pull up my pants to check my legs, which had been equally battered. But that was before I bathed in Lozen’s medicine spring. Not a mark on me now from my neck on down. Again I press my hand along the side where my ribs were badly broken. Still no pain.

“No,” I say.

“Amazing,” Mom says.

More than that, I think. I don’t tell her about Lozen’s spring. But I keep it in mind. If—no when—the day comes that I can engineer our escape from Haven, that will be one of the places we can take shelter for a while. Better that no one other than me knows about that place or the other places I have mapped inside my head. Or the caches of weapons and food I’ve been gradually building outside these walls.

Victor climbs up to sit next to me on my cot. He’s holding one of my books. I have a lot of books. I can’t say that I have a lot of friends here in Haven. Aside from Guy and my family, there’s not really anyone who’s close to me. Or anyone I care that much about.

Well, not exactly. There’s Hussein. I love his music . . . but I don’t think he even knows I’m alive. Sure, he smiles at me—that shy beautiful smile of his—sometimes when he looks up from the strings. But he smiles like that at anyone who is listening to him play. So I can’t call him a friend, or anything other than just someone to nod at, maybe say hi.

As far as other ordinary people go, I never exchange more than a word with any of them. But for some reason people keep giving me books. Word must have gotten round about my little cell library. I’ll be walking down the bloc and a woman will come up to me with something wrapped in a scarf or an old towel.

“For you,” she’ll say. “I know you will take care of it.”

And, as I always do, I’ll mutter “Thank you.” And then when I get back to my cell I’ll unwrap it and find a book like the one Victor is holding.

“I’m reading this,” he says.

That book is one of my favorites and also one of the most painful books for me to read. Black Beauty. It’s about a girl and her horse.

“What were they like?” Victor asks, tapping the picture embossed on the cover. “Horses, I mean.”

He’s only eight and thus he’s never seen a real horse. I have. But how can I explain it to him? What story can I tell? Not the real one. The one about how horses were gone from this continent for thousands of years, but then they were brought back to our people. Uncle Chatto told me that some of our elders used to say that they were the only gift ever given to us by Europe that was a welcome gift. So welcome that our horses were known by sacred names, were members of our families. We loved our horses. They loved our people. And then . . .

They called it equine pneumonia. It was worse than the normal pneumonia people get. It began at racetracks. The leaders of our nation liked horse racing and so it was one of the sports that got a lot of “scientific” attention to make it better. Dad said the sickness came about as a result of the stuff they did to make horses run faster. It was not a hormone or a drug, but an actual biological entity, a sort of symbiotic microbe. It was not injected into the blood stream, but inhaled in a mist. It didn’t just dull the pain in stressed and injured legs—like cobra venom—it actually made the horses stronger. For a while—there was a trade-off. Burn out. You got faster and stronger horses—but only for a year or two.

What happened next, though, was that the symbiote mutated. It got faster. A year or two turned into a week. The infected lungs filled with blood, yellow mucus poured out of the horses’ nostrils. And they died. Plus it turned out to be able to spread itself through the air. Fast. Any horse within ten or twenty miles got infected. And because of our marvelously efficient rapid transport networks—which made it possible to run a horse in Florida one day, put them on a 500 mph sub-oceanic maglev train and then run them in London a day later—the mutated symbiote established itself on every continent other than what was left of two-thirds-melted Antarctica within a month after it was positively identified. Too late for any quarantine to work.

So, not long before the Cloud hit us, horses had their own apocalypse. And it moved into other hooved domestic animals as well. Cows, sheep, even the semi-wild private herds of buffalos that still existed. All wiped out. The only domesticated hooved animals it spared were goats—though for some reason it didn’t affect wildlife like deer and antelope.

Which is why we are walking and running, not riding or being pulled in wagons by animals with hooves. And why the only horses Victor will ever know are in books and stories.

“Lozen?” he says. He’s waiting for me to say something.

Can I tell him how Dad and Uncle Chatto and Mom and I all had horses of our own? Poor as we were, we had horses. Which made us feel rich. On the rare days when Dad and Uncle Chatto were not working—they each held down three crappy jobs back then to just barely earn enough to feed and clothe us and pay the mortgage on our little ranch—we rode together across the mesas, racing each other and racing the wind. Or sometimes just walking along, feeling as if our horses were part of our own bodies.

My horse. I wish I could sing a song about him like those sung by my Navajo and Apache ancestors.

About his hooves striking the red earth like lightning.

About his mane whipping back like the storm wind.

About his eyes made of stars.

About his teeth made of white shells.

About his tail like a trailing black cloud.

But I do not know how to sing. Even about my own beloved horse.

We called him Black, but that was not his secret name, his sacred name. Can I tell Victor about the morning I heard the weak thudding of his hooves against the stable wall and found him on his side in his stall, trying to rise? Blood coming from his mouth and his nostrils and even from his eyes? How I cradled his head in my arms and whispered his secret name into his ear? How I leaned close to his mouth and felt the warmth of his last breath?

No.

I take the book from my brother’s hand and place my palm on its cover.

“Beautiful,” I say. “They were beautiful.”

CHAPTER

SIXTEEN

Precious Things

I wake up, as I always do, before anyone else. I open my eyes the tiniest crack, just enough to see without it being noticeable to anyone who might be watching that I am awake. I have my cot pushed back against the far wall. That way, without moving my head I can see the door of my cell. Is the bike chain still wrapped to hold it secure, the heavy combination lock still clicked shut?

Yup.

But I do not move yet. I listen. No sounds of feet sliding across the concrete walkway or of anyone trying to breathe silently as they creep closer.

Am I being paranoid? Maybe.

Am I still alive? So far.

Never imagine that you are safe when there are enemies nearby. That was Uncle Chatto’s advice. And here in Haven there are always enemies nearby.

But I don’t feel a tingling in my hands here unless those enemies are intending to do me harm, and not just keeping me under control until I can be sent out again like one of those Tomahawk missiles from the time pre-C, when anyone annoying our nation was blown up with unmanned drones and guided missiles.

Tomahawk. An old Indian word. That’s me. Their tomahawk. Their killer. But at least my missions of destruction have never involved killing innocent people (“collateral damage”). Those so-called smart bombs blew up everyone within a hundred yards of a bad guy.

I keep listening, counting silently. One and one pony. Two and one pony.

I reach one hundred. Still no sound or sight of danger, no message delivered from my Power to my central nervous system. I slide back my blanket and swing my legs onto the floor. No need to get dressed. I always sleep with my clothes on.

I sprinkle a few drops of precious water from my water container into my palms and rub my hands over my face. Then I take a small sip of water. In Haven everyone has learned how to live on the minimum amount of water possible for a human. Some have learned that lesson so well that they get dehydrated and die.

Peacemaker

Peacemaker Talking Leaves

Talking Leaves Found

Found Killer of Enemies

Killer of Enemies Wabi

Wabi Rose Eagle

Rose Eagle Code Talker

Code Talker The Long Run

The Long Run Dragon Castle

Dragon Castle The Return of Skeleton Man

The Return of Skeleton Man Pocahontas

Pocahontas Whisper in the Dark

Whisper in the Dark Two Roads

Two Roads Brothers of the Buffalo

Brothers of the Buffalo The Warriors

The Warriors The Way

The Way Sacajawea

Sacajawea Night Wings

Night Wings March Toward the Thunder

March Toward the Thunder Bearwalker

Bearwalker Skeleton Man

Skeleton Man The Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears On This Long Journey

On This Long Journey Flying with the Eagle, Racing the Great Bear

Flying with the Eagle, Racing the Great Bear