- Home

- Joseph Bruchac

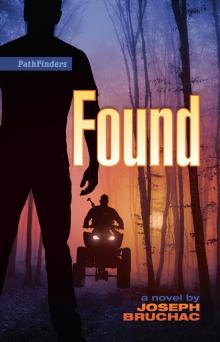

Found

Found Read online

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

on request.

We chose to print this title on paper certified by The Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC®), a global, not-for-profit organization dedicated to the promotion of responsible forest management worldwide.

© 2020 Joseph Bruchac

Cover and interior design: John Wincek

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means whatsoever, except for brief quotations in reviews, without written permission from the publisher.

7th Generation

Book Publishing Company

PO Box 99, Summertown, TN 38483

888-260-8458

bookpubco.com

nativevoicesbooks.com

ISBN: 978-1-939053-23-7

25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Contents

CHAPTER 1 Don’t Sit Still

CHAPTER 2 Stay Calm

CHAPTER 3 A List

CHAPTER 4 A Plan

CHAPTER 5 Shelter

CHAPTER 6 Fire

CHAPTER 7 First Morning

CHAPTER 8 Climbing

CHAPTER 9 The Sound of the Copter

CHAPTER 10 The Riverbank Cave

CHAPTER 11 The Roar

CHAPTER 12 Bear Song

CHAPTER 13 Going Slow

CHAPTER 14 Ferns

CHAPTER 15 They Don’t Know Me

CHAPTER 16 The Copter

CHAPTER 17 Curiosity

CHAPTER 18 Found

About the Author

To my son James Bruchac and my good friend John Stokes—real-life trackers and wilderness teachers.

CHAPTER 1

Don’t Sit Still

Sit still.

That’s usually the first rule when you’re lost. Start wandering around and you’ll just get more lost. Stay where you are. Then it’s more likely someone will find you.

But what if you’re not really lost? What if you don’t want to be found? What if being found means something a whole lot worse than being lost? What then?

Nick looked around. The stream in front of him seemed to be running from east to west toward the distant ocean. The train trestle in front of him was going north to south. High overhead, it arced like a steel rainbow between the two tunnels bored into the mountains.

But that was nearly all he knew about where he was. Except that he was somewhere between the place he’d left and the place he was going. And that he was in a wilderness area with forests and mountains all around him. He was also far from the nearest train station. How far? He wasn’t sure how long he’d been on the train before he was pushed off it.

Two hours? Three? He looked at his wristwatch. He observed where the sun was in the sky. It was still a long way from sunset. Exactly how long? It was hard to tell this time of year. This far north the days were very long at this time of year.

He’d never made this trip before, so nothing— including the trestle—looked familiar.

He could climb back up. It wouldn’t be easy, but his arms were strong enough and his balance was good. Heights didn’t bother him. He was a competent rock climber.

Get up there, then follow the tracks backward through the tunnel to an open area, and then wait for the next train. There weren’t that many. He’d looked at the schedule before getting on the train. There was one every twelve hours either going north or heading south. He could wait that long.

But so could the muscular bald man who’d shoved him out the door. He might on that train heading south. Or someone who’d been given his description might be on the northbound express. Not that a description was necessary. How many brown-skinned teenagers with a brush cut were likely to be standing by a train track in the middle of nowhere?

Nick felt as if a fist was clenched inside his chest. His hands were shaking.

Sit down. Breathe. Calm down. That was what Grampa Elie always said.

There was a big rock next to the small river. Its sides were smooth from thousands of years of water washing over it. The top of the stone was flat, shaped as if it had been made for sitting.

Nick shrugged the pack off his back and sat.

He felt himself calming down. The adrenaline was working its way out of his system.

He ran his palms over the tough canvas of the old backpack.

“Thank you,” he said to it.

Nick had always been quiet. He preferred listening to talking. According to what his parents told him, he hadn’t really started talking until he was almost three years old.

But saying thank you to his pack was the right thing to do now. It had saved his life. One of its straps had caught on a spike sticking out from the rail tie as he fell. It had stopped his fall.

That was good luck.

But the man who’d thrown him off the train had seen the pack save him. He’d been leaning over the railing at the back of the train. Just before the train disappeared into the mouth of the tunnel, that man smiled, showing his teeth. Then he made a gesture. He drew his finger across his throat and pointed at Nick.

That was bad luck.

CHAPTER 2

Stay Calm

I need to stay calm, Nick told himself.

Fear is the mind-killer. That was what Grampa Elie told Nick when Nick was only seven.

“Abenaki saying?” Nick had asked.

“Nah, it’s from one of my favorite books, Dune. Read it, Nosi. It’s a classic.”

So Nick had done just that. Even at the age of seven he loved reading. And Grampa Elie was right. The book was awesome. Then he’d seen the movies based on the book. But the book was better.

Grampa Elie hadn’t been surprised when Nick told him he preferred the book.

“Pictures are better when you make them in your mind,” he’d said. “Reading makes you think. Thinking’s always a good thing. Even when you’re scared, don’t ever stop thinking.”

Grampa Elie had been a Ranger in Vietnam. He was at a base called Khe Sanh when it was suddenly attacked from all sides at night. Unlike most everyone else, Elie St. Francis had kept thinking, stayed calm, and stayed alive.

“A lot of those other guys,” he told Nick, “were running around like chickens with their heads cut off. ‘Get down, get behind something,’” I told them. “‘Pick up your gun. Start shooting back. The enemy’s that way. Pay attention.’”

Nick hadn’t been paying attention. He’d just been feeling fortunate that he’d been able to catch a train a day earlier than his itinerary. No one would be waiting at the station on the other end until Friday. And he’d been smiling at the thought of how he would be able to make his way to Camp Seven Generations, where he’d be teaching woodcraft to other Native kids a few years younger than him from several First Nations communities. He’d get there so much earlier that no one would be expecting him yet. He’d stalk up on the place and observe everyone while staying hidden in the brush. Then, when they’d least expect it, he’d walk into the mess hall in time for dinner and tease people gently for not having guessed he was anywhere around. Didn’t any of you feel like you were being watched? It could be his first lesson for them on awareness.

But Nick was so lost in imagining what he’d do that he was unaware himself. What was it that his first martial arts teacher had told him? When a wise man starts congratulating himself, he becomes a fool. That was the reason he’d ended up this way. Maybe, too, it was because he was thinking about what he’d overheard in the dining car. Some of the other Native people in the dining car were talking about oil. They’d talked about how there was a big push to open up the reserves to oil exploration and how the people were going to resist it just like the Mi’qmaq did a few years ago over in Nova Scotia.

For whatever reas

on, he hadn’t watched where he was going. Coming back from the dining car, he’d turned right instead of left and entered the wrong train car thinking it was his. Another reason was that the train was an old one, so old that some of the locks on the sleeping compartment doors didn’t work. That was why he was able to open the wrong door, and why he saw the bald man on the floor.

Garrote.

That was the name for the thing the bald man in the black T-shirt was using. It was a length of piano wire with a piece of wood fastened on either end. It was wrapped around the throat of the man being held facedown by the bald man’s right knee. The muscles on the bald man’s arms were bulging as he pulled. A thin red line of blood was showing where the wire crossed his victim’s throat.

Nick saw it all in less time that it would take to count from one to three. But it felt like an eternity. It was as if everything was in slow motion. He was frozen, with his fingers grasping the door handle, his eyes taking in everything in the compartment. He didn’t just see the two men on the floor. He also saw the open suitcase on the bed, the brown briefcase decorated with beadwork next to the window, and the victim’s rimless eyeglasses on the floor by the right knee of the man pulling back on the garrote.

A cascade of thoughts went through his mind.

That guy’s dead. Is he Chinese? He is so dead. Back up. Shut the door. Say something. Say I didn’t see anything? Back up. Shut the door.

Then the bald man lifted his head toward Nick. He didn’t seem shocked. He didn’t seem upset. He looked up with eyes as black and cold and emotionless and dead as the water of a deep well. Then he smiled and nodded.

Nick knew what that meant. He spun around, banging the pack on his back into the wall of the narrow corridor. As he reached the end of the car, he heard a sound behind him. A compartment door was being shut.

As soon as he entered the next car, he knew he’d gone the wrong way. The car was empty. All the other passengers were in the front cars. He was at the end of the train.

Before he could turn, a hand slapped him on his back, pushing him against the wall. Two arms were wrapped around him. A bald head was pressed against the back of his neck so that Nick couldn’t try to throw his own head back and hit the man in his face. Then he was shoved through the back door of the train car.

He was held there for a moment, with his feet lifted above the floor of the platform. He tried to kick, to break free. The bald man’s arms were like iron bands. Nick felt as helpless as a kitten. He’d been taught ways to fight back, but none of them would work when he was pinned tight like this. It was dark all around them. The rattle and roar of the train was deafening. They were in a tunnel.

Suddenly there was light everywhere. They’d come out onto a high trestle between the two tunnels bored into the ancient living rock.

“Excellent!”

The bald man’s voice in his ear was calm. Even before he was hoisted up higher, Nick knew what the bald assassin had decided to do to him.

Am I going to die? he’d thought.

“It’s just business, kid. No hard feelings.” There was no more emotion in his voice than if he’d been apologizing for bumping into someone in the street. Just for a second, as the man tossed him spinning over the railing, Nick found himself looking into the bald man’s eyes. Again, he saw they were as black as the water in a deep well, emotionless and dead.

And then Nick felt himself falling.

CHAPTER 3

A List

Nick felt his heart beginning to speed up again at the memory of how close he’d come to dying.

It’s okay to be upset, he said to himself. After all, someone just tried to kill me. Acknowledge it. Accept it. Then get on with it. Do what I need to do.

He thought about the lecture he had been planning to give the junior high kids at Camp Seven Generations where he’d been heading:

When you’re trying to survive, what’s most important? Nope, not food.

Number One: Air. Without air, you’ll be dead in minutes.

Number Two: Shelter. If you’re stuck out in the sun, you’ll get heat stroke. If you’re too cold, you’ll get hypothermia. Even when it’s not freezing cold, you can get hypothermia if you just get wet and don’t dry yourself off. So you need shelter.

Number Three: Fire, if it’s cold. But you can survive in a brush shelter or a snow cave with no fire.

Number Four: Water. You can go for a couple of days with no water, but can’t go that long if you’re in a desert.

Number Five: Food. You can last a week or two without eating.

What do I have in my pack? Nick thought.

He hardly had to ask himself that. After all, he’d packed it himself. When he traveled, he always kept it close. That was why he had it on his back when he returned from the dining car. He was pretty sure he knew the contents by heart. But pretty sure isn’t good enough when your life depends on it. How many times are people pretty sure they have something with them and then find out they don’t?

Nick pulled his pack up into his lap. It wasn’t one of the new state-of-the-art backpacks made of nylon, with a lightweight frame and all sorts of watertight zipper pockets. It was made of canvas. Faded khaki green. Old, but tough.

“It’s tough like me, Nosi,” Grampa Elie had said when he gave it to Nick.

Nosi. That means “grandson” in the Abenaki language. Nick loved it when Grampa Elie called him that.

“Saved my life,” his grandfather had continued. He’d pointed at an unmended hole in the side of the pack. “Bullet went right in there, where I had stowed my lighter. Hit so hard it knocked me down, but all I got was a bruise on my shoulder blade.”

Nick ran his hand across the pack. A lifesaver, for sure, he thought. He opened the straps. He pulled out the waterproof inner bag, unzipped it, and reached inside.

He carefully laid each item on the flat boulder. First was his sheathed knife. It was on top because it was the only thing he had to put into his regular luggage when he flew. Ten inches long with a five- inch blade, it would have been taken at the first security check. Next was his compass, wrapped in a red bandanna. Then a warm, waterproof, hooded jacket that folded up small and weighed almost nothing.

Item by item he took everything else out. Cotton socks. Three pairs. Two extra undershorts. A three-meters-long roll of cord. His first aid kit. A ziplock bag of rations that held several big handfuls of shelled nuts and broken-up chocolate bars, as well as three wrapped energy bars. Three water-filtration straws. An empty, lightweight canteen. A map of the Canadian province he was in. The two watertight tins. One held the emergency kit. The other held his fire-making things. His ID was in the small wallet that also contained a single credit card and $200. There was also a roll of toilet paper in a ziplock bag. It was the one luxury he allowed himself when roughing it. Dry leaves just didn’t do the trick.

Everything he’d placed in the bag was spread out in front of him. And that, aside from what he was wearing, was all he had. His bigger backpack was still in his sleeping compartment. So was his cell phone—plugged in to recharge it.

But he had enough. More than enough. The old nineteenth-century naturalist John Muir had hiked all over America, supposedly with only a change of underwear in his bag. Then there was that big guy in those novels he loved—the former Army MP who carried nothing but a toothbrush. It wasn’t just what you had that counted. It was what you did with it. And what counted even more was what you carried in the one place no one else could see—your mind.

CHAPTER 4

A Plan

Now Nick had to make a plan. Especially since this wasn’t like the usual survival scenario. It wasn’t just a question of surviving until he could find his way out or be found. If he was found—by the wrong person or people— he’d be like that poor Asian guy who got garroted.

Ten to one Dead Eyes carried the murdered guy’s body back through that empty last car. Then he tossed the corpse off the train on some remote stretch. He’d probably cleaned up

the scene to leave no trace. Except there was one problem. One brown-skinned kid with a brush cut who’d seen what happened and had seen his face. A loose end that needed to be tied off.

Nick sat down and unzipped his hooded jacket. Its lining made it almost too warm, but it would be welcome if the nights got cold. He wiped his palms on his jeans. Not the trendy, preworn jeans with holes in them—just thick, sturdy denim. Then he spread the provincial map—which was coated with waterproof plastic—out on top of a rock and studied it. The rail line was marked on it, as were the rivers and streams that it crossed. With the elevation markers on the map, Nick had a general idea of where he was. There would be no roads—just mountains and streams to cross and days of travel. It was not an area with popular hiking trails. But if he did things right, he could find his way and reach the nearest First Nations reserve fifty miles to the east. It would be safer heading there than going north to the camp where he’d been hired as a summer survival instructor.

Why not go to that original destination?

There was a good chance that Dead Eyes had figured out where Nick was going. All the man had to do was go back one car past the dining car to find the room with Nick’s bigger bag in it. Going through it, he’d learn Nick’s name, where he was from, and his destination, if he didn’t just get all that info and more from the unlocked phone Nick had left behind.

Nick carefully put everything except the knife and one spare pair of socks back in the same order he took it out. Routine. Routine is your friend. He strapped the knife onto his belt and shouldered his pack.

He looked at the stream flowing down through the valley below the trestle.

Great.

He began to walk along the water, heading downstream. West. As he went he left footprints every now and then—not too many, but enough— in the pockets of yellow sand along its edge. He scuffed the moss on top of one stone and broke a low-hanging branch fifty yards farther down. Where the valley widened out half a mile or so farther, he turned and headed south into the woods. As he did so, he left a few footprints and more “accidentally” bent or broken branches as markers. He stopped when he came to a wide ledge of bare rock. A good place for the false trail to end.

Peacemaker

Peacemaker Talking Leaves

Talking Leaves Found

Found Killer of Enemies

Killer of Enemies Wabi

Wabi Rose Eagle

Rose Eagle Code Talker

Code Talker The Long Run

The Long Run Dragon Castle

Dragon Castle The Return of Skeleton Man

The Return of Skeleton Man Pocahontas

Pocahontas Whisper in the Dark

Whisper in the Dark Two Roads

Two Roads Brothers of the Buffalo

Brothers of the Buffalo The Warriors

The Warriors The Way

The Way Sacajawea

Sacajawea Night Wings

Night Wings March Toward the Thunder

March Toward the Thunder Bearwalker

Bearwalker Skeleton Man

Skeleton Man The Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears On This Long Journey

On This Long Journey Flying with the Eagle, Racing the Great Bear

Flying with the Eagle, Racing the Great Bear